In October of 1994, the first banner ad appeared on HotWired.com. It was a simple black rectangle with rainbow letters that read:

“Have you ever clicked your mouse right here? You will.”

AT&T paid $30,000 for it.

44% of people clicked.

That banner ad marked the beginning of a new era—one where advertising could be placed, priced, and optimized with code. And from that moment forward, a rapidly compounding ecosystem of networks, tags, pixels, and exchanges began reshaping the way we value and move attention across the web.

This is the story of how ad networks became the railroads of the internet—and how, in chasing abstraction and convenience, the industry built a system that forgot the laws of scarcity, opened the door to fraud, and divorced itself from first principles.

The Rise of the Networks

In the early web, publishers sold ads directly. If you ran a website, you either had your own sales team or left money on the table. This worked fine—until it didn’t.

As more sites came online, the long tail of content made it hard for advertisers to find inventory at scale… and for publishers to build the sales infrastructure required to facilitate that demand, directly.

Enter: ad networks. These networks acted like middlemen, aggregating supply from many publishers and selling it as packaged inventory to brands.

It was a simple trade: publishers gave up control and margin in exchange for liquidity and convenience. Advertisers got scale. Networks got arbitrage. Everyone made money.

But even then, the system already had the seed of its core problem: distance. Networks were abstractions—black boxes that pooled audiences and impressions, priced them in bundles, and obscured the real value underneath. This marked the beginning of abstractions that pushed advertisers further away from what they’re ultimately paying for.

Waterfalls and the Illusion of Optimization

As competition intensified, publishers started “waterfalling” their ad calls—routing impressions through a sequence of networks, from highest-paying to lowest, until one bidder ultimately filled it. This enabled them to facilitate demand via a sequence of partners and platforms, without missing a monetization opportunity for any placement being offered1.

On paper, this looked like optimization. In practice, it was a leaky, opaque system riddled with inefficiencies:

Latency piled up with each network hop

Most impressions were sold below their true value2

Buyers didn’t necessarily know if they were bidding first, third, or tenth, as each waterfall module appeared as an independent auction within whatever environment you had a seat at.

And worst of all: it created incentive structures that punished transparency. The more hops between buyer and seller, the easier it was to skim a few cents off the top without anyone noticing.

The waterfall was a Rube Goldberg machine of yield—over-engineered, hard to audit, and increasingly gamed by everyone in the chain.

Abstractions, Convenience, and Skewed Measurement

As the system grew, it leaned heavily on three intertwined forces:

Abstraction:

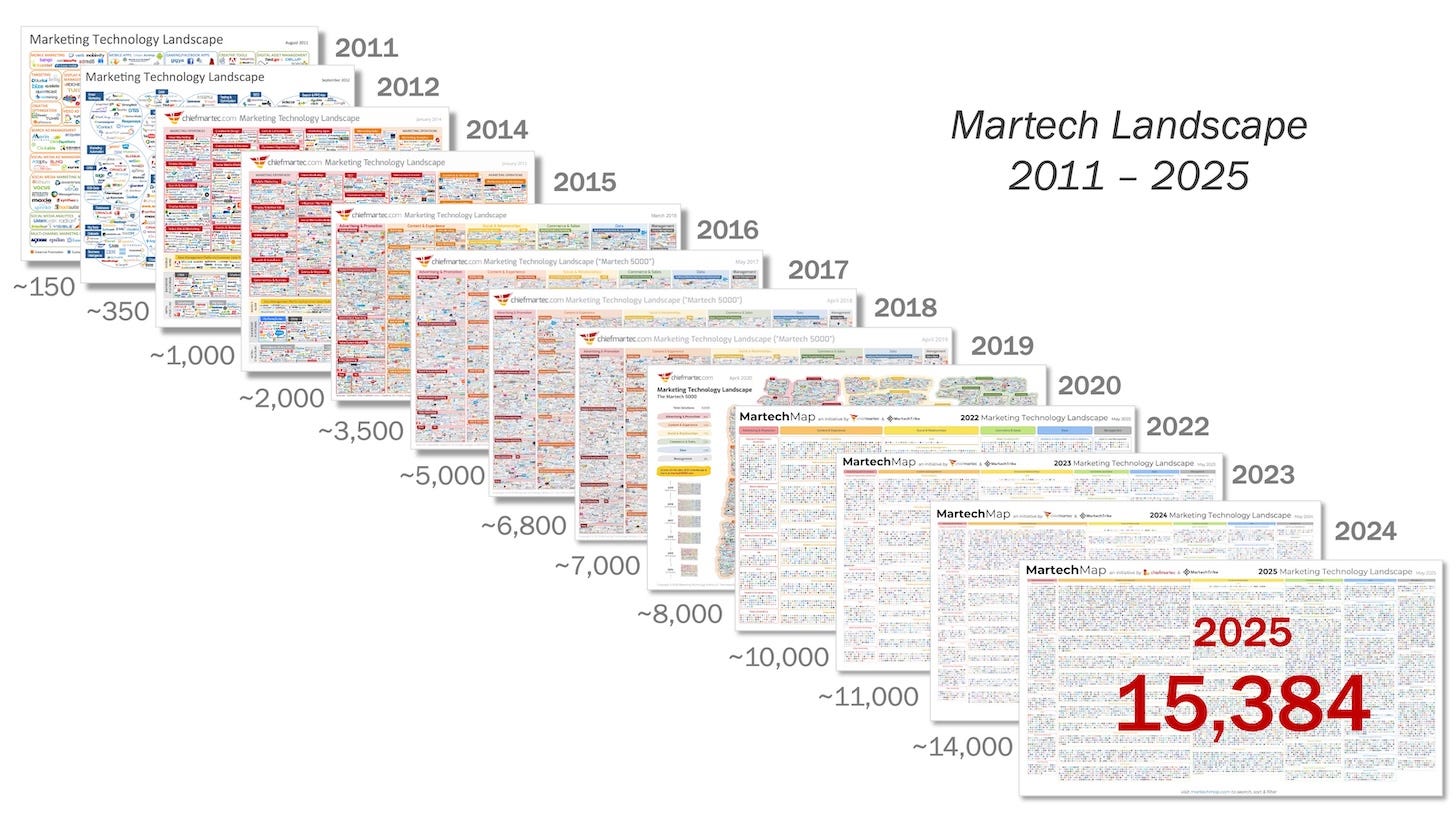

Every new tool—DSPs, SSPs, Data Onboarding Graphs, media-buying wrappers—added another layer between the advertiser and the actual user. Complexity became the product. The more abstract the system, the more dependent everyone became on intermediaries to interpret and “optimize” performance. After more than a decade immersed in this paradigm, I can confidently say: these abstractions are not just accepted—they’re celebrated with a kind of cult-like, almost religious fervor.

Convenience:

Real-time bidding systems made it easy for publishers to plug in dozens of buying ecosystems without understanding what was actually happening under the hood. One line of code could install a small army of demand hooks.

It worked too well. Publishers unknowingly enabled the buy-side through this modality to control the entire monetization framework of this industry. Buying systems became more sophisticated. Sellers stayed passive. The imbalance grew, and still grows—widening the gap through subprime interest rates on participation, where the cost is highest for those with the least leverage.

Skewed Measurement:

Everyone needed a metric, so the industry latched onto proxies: clicks, views, conversions, last-touch attribution. But these were flawed and easily gamed. Worse—they shaped incentives. Vendors optimized to whatever was being measured, whether or not it actually created value. Most of these metrics are fundamentally flawed. More often than not, the worst traffic advertisers can buy is tuned to optimize for these measurements.

As a result, entire ecosystems sprang up around exploiting the measurement system (what’s that old adage? “whatever gets measured gets managed…”).

Click farms. Cookie stuffing. Attribution theft. Fraud wasn’t a bug—it was a logical outcome of an abstraction-heavy, misaligned system.

The Death of Scarcity (and the Birth of Fraud)

In the real world, scarcity is grounding. A billboard exists in one place, seen by whoever drives past it. But digital advertising untethered impressions from time and place. With enough sophistication, you could sell the same user to dozens of bidders simultaneously—each thinking they had a shot at a unique moment, many paying for an impression never seen.

When supply isn’t scarce, value becomes fuzzy.

And when value becomes fuzzy, fraud becomes easy.

We didn’t just build a system that tolerated this—we incentivized it. Because there was always another tool, another dashboard, another layer of “optimization” to paper over the rot.

The Rise of Walled Gardens

As the open web became increasingly convoluted and fraud-ridden, a parallel system began to rise: walled gardens. Facebook. Google. Amazon. TikTok. These platforms offered an irresistible trade: vast scale, a highly engaged user-base, clean attribution, better measurement, and less technical complexity—all in exchange for one thing: control.

Advertisers flocked to them, not because they loved the lack of transparency, but because the rest of the ecosystem had made transparency too hard to use. Inside the walls, identity was persistent. Measurement was (mostly) trusted. Fraud was low (for awhile). ROI was trackable. And the buying experience felt modern.

But there’s a cost.

Walled gardens don’t just simplify—they centralize. They compress the market into black boxes where the buyer never sees the auction, the seller doesn’t know the price, and no one knows how the algorithm really works.

Worst of all: they don’t just hoard inventory. They hoard data. Every impression, every click, every conversion—captured, siloed, and used to strengthen their own targeting advantage.

Walled gardens demand a high degree of trust from advertisers—yet offer no real way to independently validate what they claim to be doing. Most advertisers either don’t realize this, or don’t fully grasp its implications.

We left the open web to escape fraud, and wound up in a prison of our own choosing.

What the Railroads Got Right (and We Got Wrong)

In the 1800s, railroads transformed economies because they solved a real, material scarcity: the ability to move goods across distance, reliably and at scale. They standardized time, created towns, and connected markets.

Ad networks (and everything in-between) promised the same: scaled access to attention. But over time, they stopped being pipes and became mazes. Instead of connecting buyers and sellers, they buried them in obfuscation.

The core difference?

Railroads made scarcity legible.

Ad tech made it disappear.

A Call for First Principles

We’re entering a new cycle—one where identity, AI, and privacy are reshaping how digital advertising works. The temptation, once again, is to add another layer rather than address the fundamentals.

But maybe the better question is: What would it look like to rebuild the system from the ground up, using first principles? Questions like:

What if we respected scarcity again? Where market prices weren’t determined by some generalized tonnage (“CPM”), but by the actual demand to reach a specific individual or segment.

What if we designed vertically integrated systems that gave equal weight to buyers and sellers—where each party controlled their own data and no single entity could exploit a constraint in the data supply chain?

What if we built systems that required zero trust to function—rather than the extremely high trust we demand from counterparties today?

What if clarity—not opacity—became the default? Where value was measured transparently, not abstracted away by proxies.

What would it take for advertisers to shift from being value sources to value captors—rebuilding the system to serve them, rather than extract from them?

Hint: Step one is owning your own data—without it, you have no leverage and no ability to effect meaningful change.

The industry doesn’t need more abstraction. It needs clarity. It needs tools that expose value—and can quantify it—not hide it. And it needs to return to a core truth:

The most powerful systems don’t just raise the bar—they lift the ground beneath us, expanding what’s possible for everyone.

—

Untitled Thoughts is a space for my writing on marketing systems, identity infrastructure, data strategy, and life as a founder building in a messy, evolving landscape. I use it to share what I’m learning, what I’m seeing, and the ideas I believe more marketers should be paying attention to—whether tactical, philosophical, or somewhere in between. If anything here resonates, I’d love for you to test drive our platform at getuntitled.ai. Your feedback makes us better.

This all happens within 15-100 milliseconds. The average human blink of an eye is 400 milliseconds.

We’ll dive into second-price auction formats in a future post and link it here once published. For the more technical programmatic folks: you likely already know, second-price auctions were a well-known arbitrage exploit in the old waterfall setup. A full breakdown of bidding formats and auction styles feels like it deserves its own post — though maybe that’s just me.